Collisions – Pitfalls, Banana Skins and Tips under English Law

Rule No 1: Never accept security without a Jurisdiction Agreement!

Unless you have a very good reason, never accept security without a separate jurisdiction agreement in relation to the underlying collision. Failure to do this can result in the ultimate check-mate where a party will potentially be in a position of having security for their collision claim, but nevertheless not actually able to advance the proceedings. In such situations the security will be of little value. The solution is simple – demand a suitable jurisdiction agreement with the security provided.

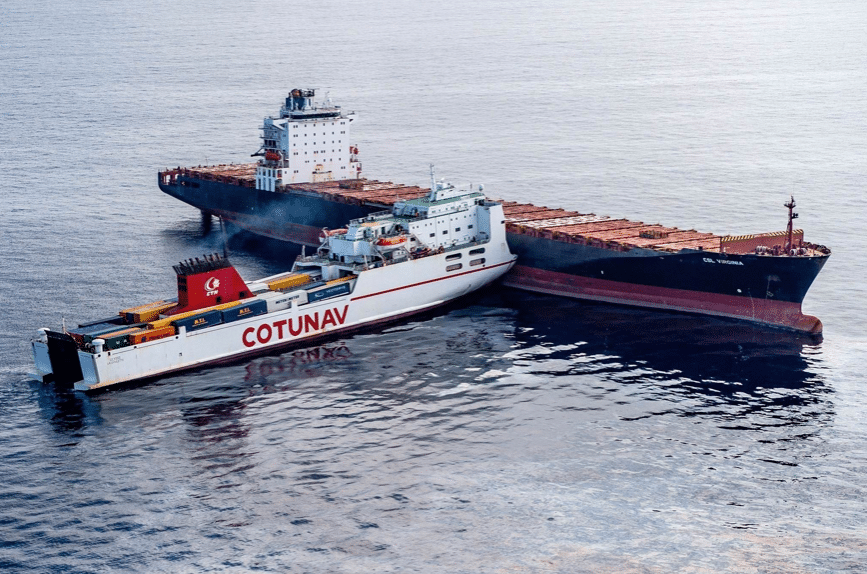

Image source: DailyMail

Whereas the solution is simple, understanding the problem is a little more involved. The key is understanding that there are two different types of claim (in rem and in personam claims) and understanding the limitations of each.

An in rem claim is simply a claim against the ship itself. It is one of a limited category of claims that can be brought against a ‘thing’, as opposed to a ‘person’ (a person being either an individual or a company).

In order to successfully commence an action against a ship, amongst other things, a party needs to take the following two steps. Firstly, they need to ‘issue’ the claim form in the English Court (this is very simple – essentially paying the fee and having the Court ‘stamp’ the correct form – although this is now done electronically). Secondly, they need to serve the issued claim form on the vessel (usually by affixing it to the vessel’s superstructure through the Admiralty Marshal). The limitation here (and the key point) is that you can only serve an in rem claim form on the vessel within the jurisdiction – that is, you cannot obtain permission to serve outside of the jurisdiction (as you might with an in personam claim). Therefore, if the vessel never comes within the jurisdiction, your claim form is potentially worthless (See The Stolt Kestrel [1]).

An in personam claim is a claim made against the ‘person’ (usually the ship-owning company and/or demise charterers – a company is a legal ‘person’ for these purposes). Again, you need to be able to do two things – issue and serve. The limitation here is that, in respect of a collision claim, you can only bring that as an in personam claim if, in simple terms:

- The collision occurred in England/Wales;

- The Defendant has his habitual residence or place of business in England/Wales;

- There is same or series of incidents already in English Court; or

- The other side submits to the jurisdiction (either by a jurisdiction agreement, or by accepting service).

Most collisions do not happen in England and Wales. Therefore, in reality, if a party does not have a jurisdiction agreement, and the other side will not accept service, it may not be possible to commence an in personam claim in England. Further, if the vessel will never come within the jurisdiction, it may not be possible to commence an in rem claim.

It may be thought that if the above factors have ruled out a claim in England, it may be possible to arrest the vessel and establish jurisdiction in another country. However, if security has been accepted, it is highly likely that the security has been given in return for a promise not to arrest the vessel (and this promise will likely be explicit within the terms of the security). This promise is, in turn, likely to prevent any subsequent arrest – quite possibly even in another country.

Nearly always there is a simple solution to prevent this pitfall: follow Rule No 1, i.e. whenever possible, always obtain a jurisdiction agreement for the underlying claim at the same time as obtaining the security. In terms of the wording, it is worth noting that the Admiralty Solicitors Group produces a standard wording for both the security and the jurisdiction agreement, along with explanatory notes. This wording then should be suitably amended to fit the particular facts of the case.

Rule No 2: Time-bar Issues

With respect to collision claims, the general position is that both vessels should correctly commence Court proceedings within the relevant limitation periods in order to prevent their claims from being time-barred.

In short, it is always safest for both of the ships involved in a collision to issue their own claim forms within the two-year limitation period (i.e. the time limit arising under Section 190(3) of the Merchant Shipping Act 1995 (the “MSA”)), and then to serve them within the necessary time-scales.

Essentially, this is because the procedure for making a counterclaim in a collision claim is unclear. Under normal (non-collision) proceedings, the general position is that any counterclaim can only be filed without the Court’s permission if it is filed with the defendant’s defence. As referred to below, the usual system of pleadings in collision cases is replaced by collision statement of the case – therefore, a “defence” as such, is not actually filed.

On one reading of the position, this would mean that it would always be necessary for a defendant in a collision claim to obtain the permission of the court to make a counterclaim. This result must be seriously doubted (because it does not accord with the practice of the Admiralty Court). Nevertheless, the safest approach to avoid any such arguments arising is for the defendant to correctly issue and serve their own claim form within the two year time-bar period. Once this is done, in practice, the two claims are effectively consolidated (albeit there will be two Court case numbers).

Time-bar issues – Collision claims, in rem & in personam, and serving in time!

It is important to understand the differences between and peculiarities of in rem and in personam proceedings. In this respect, there are important differences in:

- When these may be commenced in England (see above); and

- How and where they can be served (see above).

One further point to note is that there is no such thing as a “hybrid” claim form – i.e. a claim form that was thought to be effective to commence in both in rem and in personam – see: The Stolt Kestrel.

Rule No 3: Collision Statements of Case – Know that you are making Admissions!

Collision claims must be commenced in the Admiralty Court as “Collision Claims”. This will mean a Collision Statement of Case will replace the usual pleadings – what is the significance of this?

A Collision Statement of Case is set out in two parts. Part 1 consists of a series of questions relating to: the vessel’s maneouvres, light and sound signals given, distances, bearings and speeds of the vessel. The answers given to these various and numerous questions set out in Part 1 of the Collision Statement of Case will be treated as admissions – admissions that cannot be amended at a later point. Therefore, in order to be able to properly and carefully answer these questions, the evidence needs to be settled in a very short period of time (usually within 2 months).

Rule No 4: Expert Evidence and Nautical Assessors

In a collision claim, the Court will be guided by one or more Court appointed Nautical Assessor(s) (essentially court-appointed master mariners). What impact would this have on your collision claim?

The answer is that in relation to the expert evidence, there will be:

- No experts;

- No oral evidence (neither from experts nor the Nautical Assessors);

- No questioning (of experts or the Nautical Assessors); and

- No cross examination (of experts or the Nautical assessors).

The importance of this issue cannot be over-emphasised. In short, where there is room for differing opinions between master mariners (which, in the writers’ experience, is often…), it may not be possible to predict with any useful degree of certainty the outcome of the navigation and seamanship issues. This is because of the very limited input and influence that the parties can exercise on the Nautical Assessors.

Following a challenge under Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights (i.e. the right to a fair trial), there has been a slight relaxation of the rules outlined above relating to Court appointed Nautical Assessors. As a result, counsel may now make submissions to the judge. However, it is highly arguable that the changes made do not go far enough and the writers submit that the position is open to further challenge – this could be crucial in helping to effectively predict and influence the likely outcome of any collision claim.

It is possible to apply to the Court for the matter to be treated differently, and to try to persuade the court that normal expert evidence should be used (as opposed to the court using a Court appointed Nautical Assessor). However, if this is going to be done, it needs to be done quickly and with cogent reasoning.

Rule No 5: Easy to Forget? Don’t throw away the ‘Agency fee’!

What is an Agency fee?

When a dispute arises between the parties as to the quantum payable, do not forget ‘agency’. This is an item peculiar to collision claims and represents an accepted payment to cover the Owners’ office, post and other incidental costs and 1% of the payable claim amount is allowed.

There are many other peculiarities relating to collision claims. However, the above are some of the main banana skins to be avoided.

[1] [2015] EWCA Civ 1035