FCA COVID-19 Test Case – Business Interruption Insurance

Causation, the Orient Express and the meaning of: “Prevention”, “Vicinity”, “Event”, “Incident”, “Restriction”, “Interruption” and “Authorities”. Where this leaves us now, and other implications

In a landmark decision, the Financial Conduct Authority has pursued a test case against multiple insurers providing business interruption cover in order to try and quickly bring more certainty to the wordings of hundreds of thousands of policies.

In a long and complicated first instance judgement, the Court provided varying degrees of clarification and guidance on the interpretation of many commonly used terms in business interruption insurance policies, including:

- “Prevention”;

- “Vicinity”;

- “Event”;

- “Incident”;

- “Restriction”;

- “Interruption”; and

- “Authorities”.

The Court also considered important points of causation and disagreed with the findings of the Orient Express case, decided some 10 years ago.

This article seeks to identify the key issues considered and the main findings adopted by the Court.

Background

Judgement in this case was made public on 15 September 2020. The proceedings were brought by the Financial Conduct Authority (the “FCA”) against multiple insurers who provided business interruption cover to principally small and medium sized enterprises (“SMEs”). The purpose was to help determine whether those policies provided cover for business interruption resulting out of COVID-19 related matters.

The FCA initially had considered over 500 policy wordings from 40 different insurers, eventually bringing proceedings in relation to 21 policies. Eight insurers were invited to participate as defendants, all of which accepted.

The purpose of the case was to try to determine the relevant principles and the effect of the various types of wordings used. In this respect, the FCA recognised that there was genuine ambiguity in the meaning and effect of the clauses used.

In essence, only guidance was provided by the Court – no actual claims were determined. This was intentional. However, the judgement will have a significant impact on future individual cases, claims before the Ombudsman, and also any future disciplinary action that the FCA may decide to bring against insurers.

The position does not rest with this Court decision. On 2 October 2020, the High Court gave permission for a ‘leapfrog’ appeal to be made directly to the Supreme Court. This means that the parties are able to appeal directly to the Supreme Court and miss out (or ‘leapfrog’) the Court of Appeal. It is expected that the Supreme Court will hear the appeal by the end of the year[1]. This complicates matters, as the FCA is urging insurers to take immediate action regarding the claims which were, in effect, held to be covered. At the same time, the legal position will not be finalised until after the Supreme Court has handed down its definitive judgement. The obvious pitfall in this situation is that the Supreme Court may reverse the first instance decision (either in part or in whole), resulting in some or all of the claims not actually being covered – in circumstances where, in line with the FCA guidance, these claims may already have been paid out. That said, it is hard to fault the intentions of the FCA (if claims are not paid promptly, a significant number of SMEs may go under and disappear, rather than being helped to survive and thrive). As with many aspects of COVID-19, the situation is far from ideal, but it nevertheless requires a practical and swift response.

The case was brought by the FCA under the Financial Market Test Case Scheme. This regime[2] applies when public interest dictates that there is an immediate need for authoritative guidance on the effect of English law.

The present case falls squarely within the Test Case Scheme regime, given that, according to the FCA’s estimations, “some 700 types of policies across over 60 different insurers and 370,000 policyholders could potentially be affected by the test case.”

One point to note is that, even though the judgement provides guidance and some clarity, there is still plenty of room for argument, including the fact that (for good reason) the judgement went ahead on assumed and agreed facts – facts that might be distinguishable in individual cases.

Judgement

In the course of a complicated judgement, spanning more than 150 pages, the Court’s overall approach, in general, favoured the FCA’s wider interpretations of the various policy wordings, suggesting that cover would be provided to the assureds under a number of the disputed policies.

Each policy wording ultimately has to be examined and construed individually on its own merits based on its own particular wording and surrounding factual circumstances. However, with this proviso in mind, the Court structured its findings in the following three broad categories:

- Specified radius – local outbreaks;

- Prevention of access; and

- Causation.

Considering each of these in turn:

- Specified radius – local outbreaks

An example of the types of wording being considered was provided by what was referred to in the judgement as the Argenta 1 wording, which provided an extension of cover for:

“… any occurrence of a NOTIFIABLE HUMAN DISEASE within a radius of 25 miles of the PREMISES …” (emphasis added)

One of the general arguments put forward by insurers was that, if any occurrence of COVID-19 identified was outside of the prescribed policy area (in this case 25 miles), then the cover should cease to apply. The reasoning behind this argument was that the cover referred to occurrences happening within the policy area, and, as was (in some cases) argued, only within the policy area.

This point arose in the context of various policies and the Court took the view that the relevant cover was triggered so long as the fortuity prescribed under the policy occurred within the policy area, regardless of the fact that the same also occurred outside the limits of this area.

It should be noted that the Court considered crucial the fact that the wording of this extension did not expressly state that a notifiable disease should occur only within the 25-mile radius prescribed. Had there been a specific clause to that effect, the position may have been different. This reflects the principle of ‘freedom of contract’ under English law[3], whereby (subject to certain exceptions, such as illegality and liability for death or personal injury) commercial parties are free to agree what they like, and the Court will give effect to that – provided that the words used are clear enough. That said, the more unusual the outcome, the clearer the parties need to be[4].

- “Prevention” of access

An example of the types of prevention of access wording under consideration was provided by what was referred to in the judgement as the Arch wording, which stated:

“We will also indemnify You in respect of reduction in Turnover … resulting from…

Prevention of access to The Premises due to the actions or advice of a government or local authority due to an emergency which is likely to endanger life or property …” (emphasis added)

As will be apparent, one of the main points discussed in the judgement was the extent of the “prevention” required and, in particular, whether this would be satisfied by a mere ‘hindrance’.

The Court considered the parties’ positions but decided to follow previous case law. In essence, the Court generally took the position that ‘prevention’ encompassed ‘impossibility’, as opposed to ‘hindrance’ (which denotes something difficult, but not impossible).

In the context of the Arch wording, the Court found that prevention required that the premises must be closed for the purposes of carrying out the business – however, this did not entail there being a physical impossibility preventing physical access to enter the premises, but “prevention” could be satisfied even if access were, in fact, possible – for example, for maintenance purposes. The Court gave the instructive example of a restaurant which, along with its in-restaurant dining service, had takeaways forming also a substantial part of its business. Although the restaurant would not be allowed to carry on with its in-restaurant service, it would be perfectly able to carry on with its take-away services. Therefore, there could not be said to be a total closure and, as a result, “prevention” of access – rather there was merely a hindrance in the performance of the services.

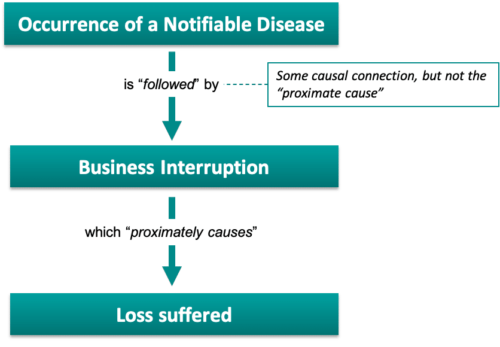

- Causation and the use of the word “following”

The Court also considered the causal connection required in certain circumstances where the word “following” had been used. This issue was illustrated in one of the policy wordings – the RSA 3 wording, which stated:

“We shall indemnify You in respect of interruption or interference with the Business during the Indemnity Period following … any … occurrence of a Notifiable Disease within a radius of 25 miles of the Premises;” (emphasis added)

The Court considered that causation in these circumstances was formulated as follows:

- The business interruption or interference needed to ‘follow’ an occurrence of a Notifiable Disease (but it did not need to be proximately caused by it); and

- The loss suffered needed to be ‘proximately caused’ by the business interruption or interference.

The position can be summarised diagrammatically as follows:

The Court’s reasoning was founded on the meaning of the word “following”. The Court took the view that “following” did indeed denote a causal link – but only between the occurrence of the Notifiable Disease and the business interruption. However, this causative relationship did not amount to the requirement of proximate causation (i.e. “following” denoted a more loose causal connection).

“Proximate causation” is introduced by Section 55(1) of the Marine Insurance Act 1906, which states:

“… the insurer is liable for any loss proximately caused by a peril insured against, but, subject as aforesaid, he is not liable for any loss which is not proximately caused by a peril insured against.”

It has been held that the “proximate” cause “is not the cause nearest in time to the loss but the “efficient” or “dominant cause””. A useful illustration of this point is the House of Lords decision in Leyland Shipping Ltd v Norwich Union Fire Insurance Society Limited [1918] AC 350.

In that case, a vessel’s insurance policy provided cover for “perils of the sea”. The same policy contained a warranty against “hostilities”. In the events that transpired, the vessel was struck by a torpedo. However, the vessel eventually sank as a result of the action of the waves at the place where she lay. In determining the cause of the vessel’s loss, the Court had to consider whether the loss was caused by the torpedo (i.e. where the loss would not be covered) or by the action of the waves (i.e. a ‘peril of the sea’, in which case the policy would provide cover). The Court held that, although the cause nearest to the loss of the vessel was the perils of the sea, this was not the proximate cause of the loss. Instead, the true proximate cause of the loss was the effect of the torpedoing.

Importantly, in relation to the issue of causation, the Court considered the applicability of (and, indeed, the correctness of) the Orient Express case[5] – particularly given that the insurers relied heavily on this case in the course of their arguments.

The Orient Express case

This was a case involving business interruption losses. In this case, the assured was, in part, covered for business interruption arising from damage to the hotel. The assured hotel owners claimed to be entitled to be indemnified by their insurers following damage suffered by their hotel and the surrounding area resulting from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. The insurers refused to indemnify the hotel owners under the business interruption provision of the policy, in part, on the basis that the hotel would have suffered the business interruption regardless of whether the hotel suffered physical damage, due to the overwhelming effect of the hurricanes in the surrounding area. The High Court in the Orient Express, for a number of reasons, agreed with the insurers’ position.

It can be seen that, if the Orient Express decision is correct, it might be used by analogy in cases involving COVID-19 if, for example, cover was provided for business interruption arising out of closures due to local COVID-19 restrictions.

The High Court in the FCA case concluded that the decision in the Orient Express was wrong. In particular, the judge in the Orient Express had failed to correctly identify the insured peril. In their view, the judge in the Orient Express case identified the damage to the hotel as the peril insured, when, in fact, the policy was an “all risks” policy and the relevant peril should have included the hurricanes. Hence the Court should not have been concerned with business interruption caused only by the damage, but instead the Court should have been concerned with business interruption arising from damage which itself was caused by hurricanes. In this way, logically, the correct question to be asked was whether, “but for” the damage caused by the hurricanes, the hotel would still have suffered business interruption (as opposed to what the High Court in the Orient Express case asked, which was whether, “but for” the damage, the hotel would still have suffered business interruption). However, it is not clear how this advances matters, as it seems that the relevant test still links directly to business interruption losses arising as a result of damage (albeit damage caused by hurricanes). Had the hotel suffered no damage but the surrounding area was badly affected, it is difficult to see how this portion of the cover would bite. In reality, the relevant business interruption was caused largely by hurricanes, regardless of the damage.

In any event, it is clear that the Court in the FCA case was heavily influenced by the arguments that the effect of the Orient Express case was that the wider the damage suffered generally, the less cover was provided. Had the hurricanes damaged only the hotel, then there would have been no dispute as to coverage. However, in the circumstances where the hurricanes also damaged the surrounding area, cover for business interruption was refused. In the Court’s view, that was not something that the parties could be taken to have intended.

In light of the High Court’s findings in the FCA case, the Court held that the decision on the Orient Express had been wrong. In any event, the Court held that the Orient Express decision was distinguishable because the perils being considered were different and, therefore, they did not need to resolve the difficulties that case presents.

The position in the Orient Express case is, in fact, complicated further by the fact that the relevant policy had:

- Separate cover for Prevention of Access (POA) and Loss of Attraction (LOA) – which would have clearly covered business interruption loss by hurricanes not involving damage to the hotel itself. However, the assured did not wish to rely on this, due to the lower limits of cover; and

- The policy had a ‘Trends’ clause that reduced the cover in respect of circumstances “…which would have affected the Business had the Damage not occurred…”.

The arguments which the Court in the FCA case applied to address these aspects of the reasoning of the judge in the Orient Express were not particularly convincing.

In similar cases, where similar issues and policy wordings arise, the stage is set for further challenges. It is hoped that the Supreme Court will apply their collective brain power to the issues raised by the Orient Express and bring clarity.

Further points considered in the Judgement

Conflict between an express cover extension and an exclusion clause in the policy

Under what was referred to in the judgement as RSA 3 wording, there existed what appeared to be a conflict. On one hand, the main policy wording expressly covered any business interruption or interference resulting from a “notifiable disease”. On the other hand, the policy appeared to exclude losses or damage arising out of epidemics and diseases under the General Exclusion Clause.

Applying the English law principles of construction, the Court considered this apparent conflict and held that the General Exclusion Clause should be read in a way so as not to defeat the cover expressly provided under the Extension Clause. The Court stated:

“We have no doubt that a reasonable person would not understand the insurance to be expressly giving cover with one hand and taking it away by the other in the form of the list of matters referred to in General Exclusion L.”

The result is hard to argue with.

The meaning of “vicinity”

In some of the policy wordings considered, the insured peril was covered so long as it occurred within the “vicinity”.

By way of example, in what was referred to in the judgement as the RSA 4 wording, Clause 2.3 of the “Specified Causes” provided cover for business interruption resulting from:

“Notifiable Diseases …

…

occurring within the Vicinity of an Insured Location …” (emphasis added)

The meaning of the word “vicinity” was defined in the RSA 4 policy as follows:

“Vicinity means an area surrounding or adjacent to an Insured Location in which events that occur within such area would be reasonably expected to have an impact on an Insured or the Insured’s Business.”

In relation to “Vicinity”, the Court stated that:

“… in relation to a disease such as COVID-19, an extensive area, possibly embracing the whole country, can be regarded as the relevant Vicinity for the purposes of this wording.”

On one view, arguably, the RSA 4 wording above re-defined the meaning of the word “vicinity”. However, where the word “vicinity” was used in a more limited context, such as in the Zurich 2 wording (see below), the result was in stark contrast. In what was referred to in the judgement as Zurich 2 wording, it was stated that:

“Action of competent authorities

Action by the police or other … authority following a danger or disturbance in the vicinity of the premises whereby access thereto will be prevented …” (emphasis added)

In this wording, the “vicinity” was held to denote a specific area, clearly localised and near the centre point of the insured peril. As the Court stated:

“… the overall phrase “a danger or disturbance in the vicinity of the Premises” contemplates an incident specific to the locality of the premises rather than a continuing countrywide state of affairs.”

This is a good example of why each wording needs to be considered separately and in its own, often unique, context. The wordings are very similar, but the effects are potentially very different.

The meaning of “event” and “incident”

A further point under consideration by the Court was the meaning of the word “event”. An example of the use of this word can be found in what was referred to as the QBE 2 policy wording, which provided cover for:

“… Loss resulting from interruption of or interference with the business in consequence of any of the following events …” (emphasis added)

The Court considered the meaning of “events” and concluded that (pursuant to Lord Mustill’s dictum in Axa Reinsurance v Field [1996] 1 WLR 1026) an “event” is something which occurs “at a particular time, in a particular place and in a particular way”.

Along the same lines, the Court also considered the meaning of the word “incident”. This was elaborated on in the context of what was referred to as the Hiscox Ndda policy wording, which provided insurance cover for:

“… an incident occurring … which results in a denial of access or hindrance in access to the insured premises, imposed by any … authority …” (emphasis added)

Drawing a distinction from other wordings, such as “emergency” or “danger”, the Court held that an “incident” was more akin to an “event” – i.e. something with specific geographical and temporal coordinates and occurring in a particular way. In this respect, the Court gave examples of a bomb scare or a gas leak or a traffic accident.

In light of the above, the Court accepted the insurer’s position that, although COVID-19 could sit well with the requirements of an “emergency”, it could not be considered to be an “incident”, as it was “too geographically dispersed, variegated, prolonged and non-specific to amount to an incident.”

The approach taken by the Court highlights that the particular wording adopted by insurers (even if, at first blush, quite similar – for example, the use of “emergency” versus “incident”) can have dramatically different effects on the extent of the actual cover provided.

The meaning of “interruption”

In the course of its judgement, the Court provided clarification regarding the meaning of “interruption”.

The interpretation of the word “interruption” by the Court, again provides a useful example of how the context in which the word is used is all important.

In the context of what was referred to as the MSA 2 policy, “interruption” was held to denote a complete cessation of the business – i.e. a mere disruption in the operation of the business would not suffice. The MSA 2 wording provided cover for:

“… financial losses and other items specified in the schedule, resulting solely and directly from an interruption to your business …” (emphasis added)

Contrary to the findings regarding the MSA 2 wording, in considering other policies, the Court concluded that ““interruption” … in Hiscox 1 and Hiscox 4 is to be interpreted as not being limited to complete cessation but as including disruption to or interference with the business.” In reaching this conclusion, the Court considered various provisions, including the loss of attraction and the NDDA provision in the Hiscox policies and concluded that, reading the policy terms together, Hiscox’s wording of “interruption” extended beyond complete cessation of the business and included disruption.

The meaning of “restriction”

The Court also considered the meaning of “restriction”. An example of this wording was set out in what was referred to as the Hiscox 1 policy wording, which provided cover to the assured for:

“… financial losses … resulting solely and directly from an interruption to your activities caused by:

…

… your inability to use the insured premises due to restrictions imposed by a public authority during the period of insurance …” (emphasis added)

The Court concluded that when the words “restrictions imposed” are used, the aim of the policy is to allude to something mandatory, i.e. something which has the force of law. The Court’s view was reinforced by the use of the word “imposed”. Applying this logic, it would be difficult to see how an advisory wording (no matter how strongly put) could denote a ‘restriction’ being ‘imposed’.

The meaning of “authorities”

A very interesting point that was considered in the course of the judgement, was the meaning to be given to the word “authorities”.

In what is referred to in the judgement as the EIO Type 1.2 policy wording, the prevention of access provision contained an exclusion of cover in respect of prevention of access caused by:

“… closure or restriction in the use of the premises due to the order or advice of the competent local authority as a result of an occurrence of an infectious disease …” (emphasis added)

The Court considered the meaning of “competent local authorities” and concluded that it would be unlikely that the parties purported to afford cover only for actions or advice of local authorities – this would be an “artificial and illogical result”. Instead, the “competent local authorities” were held to include any authority which can impose actions or provide advice in relation to any occurrence of the disease in the locality. The scope of these “authorities” would, therefore, also include central government.

The Court’s conclusion that “local authorities” should also include central government may appear, on a literal interpretation, surprising. However, the Court’s reasoning is not without logic. In construing the policy wording, the Court considered the relevant legislative background and determined that, if “authorities” were to include local entities, the scope of the wording would be limited beyond that which the parties likely intended.

Effect of the Judgement

The judgement will have a significant impact both in terms of the law, but also in terms of the regulation of insurers.

Legal effect

The judgement sets out general principles in relation to the proper construction of insurance policies and the extent of coverage.

Despite the fact that the Court relied on specific policy wordings, the market implications for the use of such wordings is expected to bring a significant shift in the way both the insurers and the assureds approach coverage wordings. Insurers can make use of the judgement to help ensure sensible limitations on coverage. Equally, assureds advised by competent brokers will be able to help ensure that their coverage is sufficient.

Broadly, as a result of the decision, insurers may well prefer the use of the terms “prevention” of access and “incident”, whereas assureds may prefer “hindrance” of access and “emergency”. However, much will depend on the precise wording used, particularly when using phrases such as “vicinity”.

Nevertheless, the legal effect of the judgement is currently, to some extent, ‘fluid’. Only after the Supreme Court hands down its judgement, confirming or rejecting the reasoning applied by the first instance judges, will the insurance market be in a position to better assess the long-term implications of the judgement.

Regulatory effect

The FCA is the regulatory body in charge of supervising insurers. In its letter dated 18 September 2020, the FCA set out its expectations from insurers in light of the judgement. In particular, the letter makes clear that the FCA expects insurers to “reassess and settle claims quickly, including making interim payments wherever possible on policies where the legal process is complete or the claim has been accepted in full or in part”.

Insurers are excepted to:

- Finalise any outstanding claims with the assureds;

- Take the judgement into consideration in assessing and in reassessing claims which may have been affected by the judgment – unless these have been fully and finally settled;

- Consider whether government support, such as the furlough schemes, should be deducted whilst adopting a fair treatment approach (this is subject to the circumstances of each individual case);

- Inform the assureds regarding next steps in a clear manner; and

- Update the FCA regarding insurance contracts which are affected by the judgment.

It is worth noting that the FCA has stated that it will not seek to apply the judgement ‘retrospectively’ – that is to say, it will not punish insurers for refusing cover for claims on the basis of the perceived legal position prior to the judgement.

The effect of Government support

Although there is no unitary approach to be undertaken in assessing whether the government support should be deducted from the indemnity to be paid by the insurers, the FCA expects the insurers to treat their assureds in a fair and honest way when examining the surrounding policy terms and circumstances of each insurance contract.

Wider applications

The effects of the judgment could potentially go beyond the strict limits of insurance law, and affect the approach taken by the Courts in various different types of contracts.

One example would be in the context of a ‘force majeure’ clause. This is a clause whose typical effect is to allow a party to a contract to be excused from performing its obligations, at least for a period of time, when a specified occurrence takes place.

It is not uncommon for ‘force majeure’ clauses to include a wording along the following lines:

“Neither Party shall be liable for any loss, damage or delay due to any of the following force majeure events which could not reasonably be foreseen at the time of entering into the Contract to the extent the Party invoking force majeure is prevented or hindered from performing any or all of their obligations under the Contract[6]”. (emphasis added)

It is clear that this type of wording could be affected by the decision in the present case. Both the discussion over the meaning of “event” (see also the comments in relation to “incident”), as well as the scope of “prevention” could provide useful guidance in determining the meaning of these words in the context of COVID-19.

Conclusion

Given the speed of the proceedings and the breadth of the different policies and wordings covered, the parties are to be commended for what is undoubtedly a very practical and helpful case.

The combination of the effective use of the Financial Market Test Case Scheme and the constructive cooperation between the insurers and the regulator are a great example of the industry coming together to find fast, and practical solutions.

By no means are all of the uncertainties resolved, and the position remains in a state of flux, at the very least until the Supreme Court has ruled . However, even so, far greater clarity exists now than was previously the case.

The position will continue to be refined and provide more accurate means of managing risks, particularly in respect of, dare we say, future pandemics.

[1] UPDATE 2-FCA insurance test case appeal heads to Supreme Court (https://www.reuters.com/article/britain-insurers-court-idUSL8N2GT4DC)

[2] Previously regulated by Practice Direction 51M and currently under Practice Direction 63AA of the Civil Procedure Rules.

[3] See for example Photo Production Ltd v Securicor Transport [1980] A.C. 827, where Lord Salmon stated that “[a]ny persons capable of making a contract are free to enter into any contract they may choose: and providing the contract is not illegal or voidable, it is binding upon them.”

[4] For illustration purposes, see the Court of Appeal decision in Stocznia Gdynia SA v Gearbulk Holdings Ltd [2009] EWCA Civ 75, where Moore-Bick LJ stated that “[t]he court is unlikely to be satisfied that a party to a contract has abandoned valuable rights arising by operation of law unless the terms of the contract make it sufficiently clear that that was intended. The more valuable the right, the clearer the language will need to be.”

[5] Orient-Express Hotels Ltd v Assicurazioni Generali SpA [2010] EWHC 1186 (Comm); [2010] Lloyd’s Rep IR 531.

[6] See for example a variation of this wording in Clause 16 of the BIMCO Bunker Terms 2018 and in Clause 14 of the BIMCO DISMANTLECON form.